Managing Military Veterans in Collision Repair Shops

As we celebrate Independence, we honor the men and women of the U. S. military who gave their lives for our country, ensuring our continued independence. But it’s important to realize many military veterans have returned home and need gainful employment. The collision repair industry offers great career options for military veterans, who offer unique skills that can bring a lot of value to shops; however, some shop owners hesitate to hire veterans due to misconceptions or simply a lack of understanding about what the skills on a military vet’s resume actually mean!

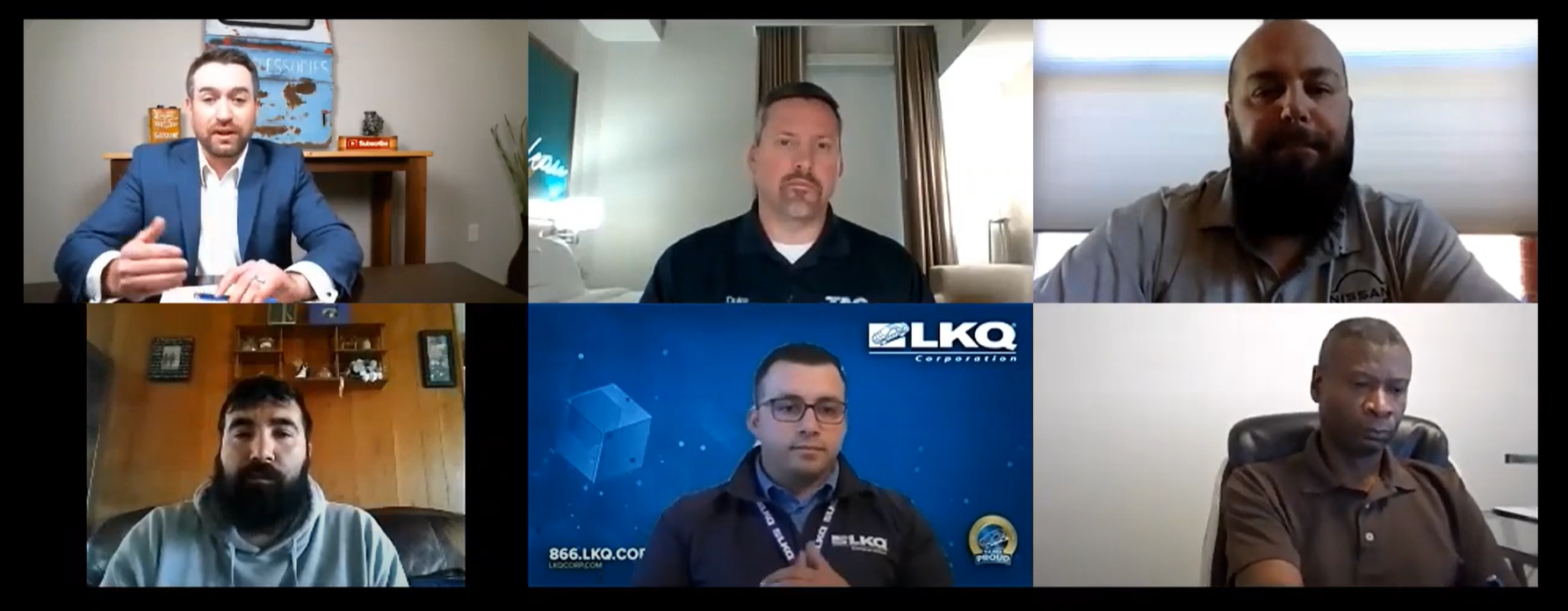

WrenchWay addressed some of these concerns during a recent roundtable, “Managing Military Veterans in the Shop,” moderated by Jay Goninen, president of WrenchWay. Five military veterans currently working in shops and other segments of the industry served as panelists, including:

- Duke Fancher, VP of Aftermarket, Lonestar Truck Group/TAG (Army),

- Charlie Shephard, Senior Business Analyst, Rutterkey Solutions (USMC),

- TC Olsen, Director, Talent Acquisition, LKQ Corporation (Army),

- Marc Babcock, Service Manager, Lithia Nissan of Eugene (USMC), and

- Michael Olivias, Lead Technician, American Jewelry & Pawn (USMC).

Panelists began by discussing the traits that military veterans offer, which add value to shops. Flexibility, adaptability, and punctuality were commonly mentioned traits. Shepherd pointed out, “Typically, vets have been in situations where they’ve had to adjust quickly, so they tend to have a can-do attitude and are always up for a challenge. They understand how to follow basic structure and procedures, but they can also think outside the box to accomplish what needs to be accomplished.”

The two techs, both vets, working under Babcock always “go the extra mile. They find everything wrong, not just the first thing,” he said. “Customers had told me that they received their vehicle back in better condition; that’s how much effort my guys put into making sure they do their best on every job.”

Olivias agreed: “I’ve known a lot guys who were okay with being C-level techs, but every vet I’ve worked with had the drive to improve. I love seeing the guy next to me eager to learn, so he can become as competent as possible.”

“Vets aren’t afraid of training; training and discipline are instilled in our way of life,” Fancher added. “There’s not much quit in military-trained guys and gals, and they’re used to getting the job done with limited resources. We also have unspoken rules about being there for each other in the field. Those values come with hiring a vet, but it’s not something you’re going to see on a resume.”

Explaining that military training also includes leadership skills, Olsen stressed, “It’s important to measure those competencies when you’re seeking or interviewing a candidate. Some traits may not be written on a resume, but if you read between the lines and look at their service, you’ll know they can handle anything you throw at them. You may need to include other vets in the hiring process to help you determine which competencies might make that person a good fit, so you understand what they can bring to your shop.”

Fortunately, the military’s Transition Assistance Program (TAP) places “an extreme amount of emphasis into resume writing and making us more promotable to the civilian job market,” Babcock stated. “They help us equate our military experience to shop skills, plus they teach us what to wear, to be well-groomed, and even how to interact professionally because they want us to promote ourselves the best we can. Then, they bring in instructors and senior military members to hold practice interviews. Don’t be surprised if a vet shows up for a shop interview in a full suit!”

TAP also teaches vets about social media, but the biggest challenge is “learning how to stick out when you’ve been taught to blend in,” according to Olsen. “A great tactic for veterans is to stay close to the network you already have so you don’t land in the abyss of applicant pools. Learn how to integrate into that network, and then stand up confidently and stand out professionally.”

One challenge military veterans face when seeking employment comes in the shape of stereotypes: inexperienced, uneducated, ineffective communicators. “Most people’s only experience with a Marine is the drill sergeant from Full Metal Jacket, and that’s what they’re expecting,” Olivias joked. “I have a customer-facing role, and my manager questioned whether I’d be able to politely and effectively communicate with our high-end customers who are used to being served.”

Agreeing that a lack of communication skills is a common misconception about vets, Olsen emphasized, “We’re taught to communicate, whether it’s authoritatively or in another manner. A lot of stereotypes about veterans result from misunderstanding, but you’ll never understand until you talk to them and really measure their skills against what you’re trying to accomplish.”

Fancher suggested that shop owners can access personality assessments and other resources that help determine whether a person is a good fit for the business. “I’m an outgoing guy, so my personality was slightly modified in the military,” he admitted, “but it didn’t change who I was at the core.”

Shephard sees the stereotypes from an alternate angle: “Some guys worry that veterans will set the bar too high, work too hard, and make them look bad, but sometimes, you need to get that better man in the shop to get the rest of your team to step up their game and accomplish more! Don’t just overcome those stereotypes; use them to your advantage.”

Returning to the subject of communication, Goninen shifted to ask panelists how shop managers should provide feedback and constructive criticism to techs who served. According to Shephard, “Vets like direct feedback, especially when they’re straight out of the military, but as they become more acclimated to civilian life, remember that they’re individuals and tailor the communication to them.”

Observing that veterans are accustomed to getting instant feedback, Olsen said, “When you don’t get that constructive feedback in the corporate world, it can be a challenge because we want to learn and grow. A lot of vets thrive on the challenge, and we thrive on feedback, whether it’s good or bad. Sometimes, the bad feedback is what’s best because it helps us grow.”

On the subject of attracting veterans to the shop and then retaining them, shop culture is just as important to military veterans as to civilian technicians, if not more so. Olivias, who served under Shephard, recalled, “When I was a baby, Charlie welcomed me, got to know me, and set expectations for my role. That really stuck with me, and when I was in management, I’d always take the new guy out to lunch to let him know I’m paying attention and that I’m there if he needs me to be.”

Similarly, Babcock is “constantly walking around the shop to get a feel for what’s going on. I’ll chat with the techs to find out what’s bothering them, what’s good, and what we can do better. My techs feel wanted, and they’re comfortable talking to me or sharing something they’ve learned. I think it’s really important for managers to have an open-door policy.”

Fancher recommended partnering a newly hired veteran with a tenured associate for mentorship purposes. He also indicated that having a clearly defined career path is helpful. “It should be transparent, so they understand what they need to do to get to the next level, and when they’ll receive a raise. We also need to review performance faster and more consistently than once a year. Set clear expectations to get predictable results.”

Olsen agreed, “Veterans want to hear about structure because it allows them to prepare for success, and if you give them guidance along the way, they’re going to bust their tails.”

Of course, all veterans cannot be placed in one box, treated identically, and expected to behave the same – everyone is different, even when they have a military background in common. Babcock pointed out, “The five of us have different backgrounds, and we’re completely different people. We’re acclimatized to different things, but we’re used to change, plus we’ve changed so many times that it makes us better in a shop: as a tech, as a service advisor, or as an owner. We easily adapt to how frequently the market changes.”

Olsen concurred, “Everyone’s different, and there are so many layers of experience you’ll discover if you get past any initial bias.”

“We may have experienced a lot of the same things in the military, but we experienced some of them differently because we’re all different,” Shepherd contributed. “We’re people first, so we’re unique, but compared to civilians, military veterans bring different things to the table in terms of what we’ve physically done, experienced, and been exposed to.”

Panelists encouraged shop owners interested in hiring military vets to post job opportunities with their local TAP office and schools, but many other organizations exist for the purpose of connecting military veterans with potential employers, some specific to the region of the employer.

Goninen ended the roundtable by thanking the panelists for their service. WrenchWay’s Managing Military Veterans roundtable recording is available to watch here.